Udacity Self-Driving Car Nanodegree Final Project, Part 2 - The Git Master

This is Part 2 of my account of the Udacity Self-Driving Car Engineer Nanodegree program’s final project. Read Part 1 here.

I left off last time right at the starting gate. I’d gone through the lesson material and the final project description and instructions. The next step was to browse through a shared spreadsheet and find a team with an open slot, or create a new team if there were no open slots. (If nothing else had tipped me off so far in the past year, I could definitely tell that Nanodegree students are my kind of people from this spreadsheet - all slots had been filled on all teams all the way down to the bottom of the list, just like you’d wish people would fill seats at a theater.) I filled the fourth slot on the last team listed on the page, Team Bacon. Sounds like my kind of team - nobody’s taking themselves too seriously on Team Bacon, that’s for damn sure.

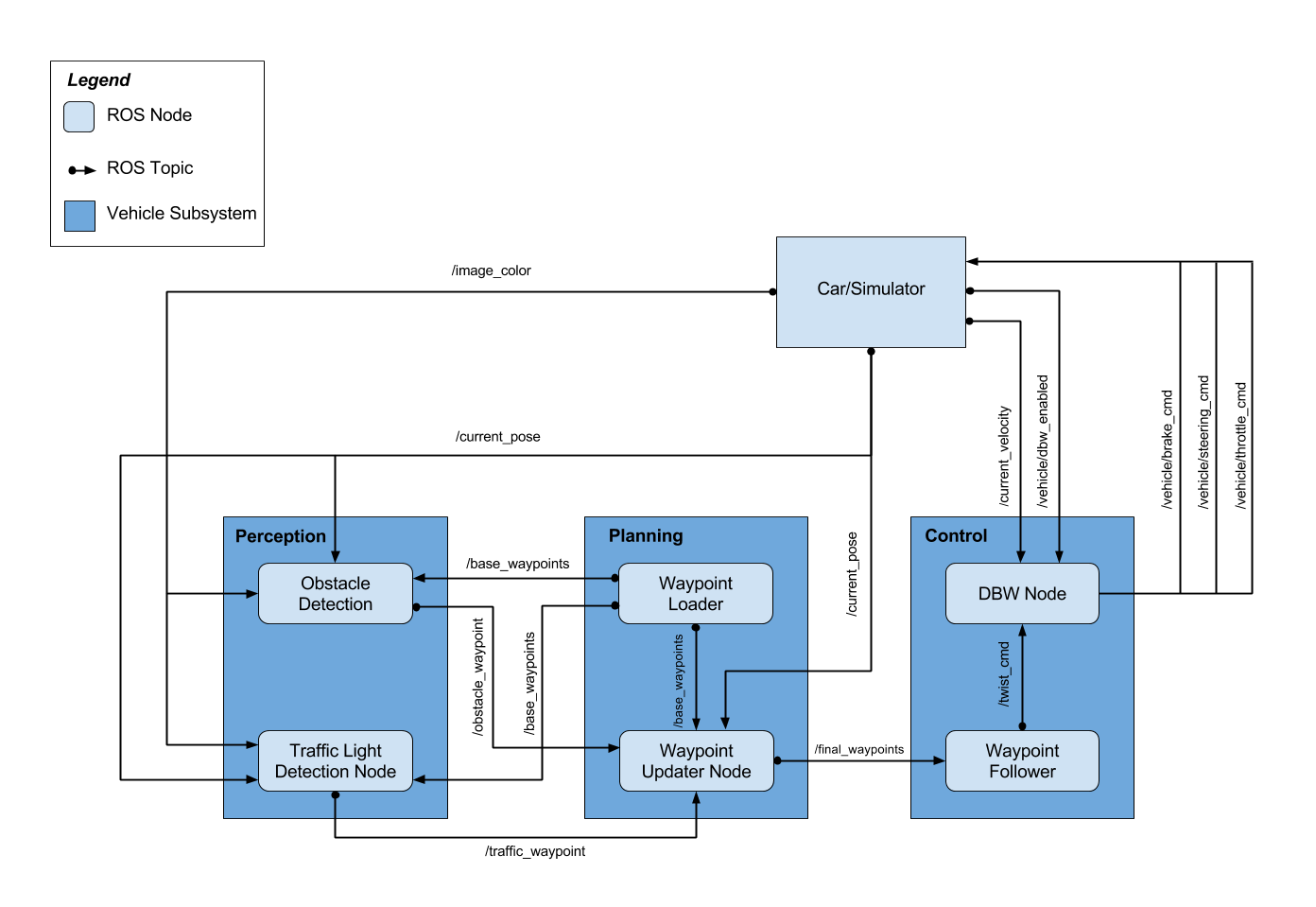

I e-mailed my five new teammates, who happened to be scattered across the United States and Europe, and we set up our first conference call. We discussed the project and made sure we were all on the same page and understood what needed to be done. Then it was time to volunteer for tasks. If I may remind you of the project block diagram:

The tasks available were:

- Waypoint Updater node (first pass)

- DBW node

- Traffic Light Detector node

(read more about these in Part 1)

Typical of me, I waited for others to choose their tasks before volunteering for whatever might be left (if we’ve ever been to an office potluck together, you’d have surely noticed me waiting for the line to dwindle down to nearly nothing before queueing up myself; I might miss out on some hashbrown casserole, but I don’t really mind). I had assumed all along that I’d be handling the vehicle controls in the DBW node, mostly because computer vision and machine learning seemed so popular among other Nanodegree students. To my surprise, two of my teammates immediately signed up for the DBW node. The team leader then chose the Waypoint Updater node, and another teammate chose the Traffic Light Detector node. I decided I would help out with the Waypoint Updater node to start with, since it was the first order of business, then move on to help with the Traffic Light Detector node afterward.

We created our team repo on GitHub, cloned the Udacity starter code, and we were off. Each team created a branch in which to implement their feature. By the time I was ready to start work on the Waypoint Updater node, I’d found that my team leader (because he was several time zones ahead of me) had already finished the first pass at it. What?! Not only that, but a good chunk of the DBW node was complete as well. My teammates were ready to merge their changes into the master branch and they either hadn’t done such a thing before or they were going to bed (the Europeans, anyway). It was up to me, and the only such experience I’d had was while messing around with branching and merging in Team Foundation Server. All of my work projects had only ever been in individual repositories, if there were any sort of central repository at all! I’d figure it out, though. Here I was, Team Bacon’s… Git Master! (How cool does that sound?)

A lot of my merging happened right there in the GitHub web interface, mostly because I was away from home at the time. I was surprised at how easy it was to merge whenever there were no conflicts. Just press the button and it was done. This was useful any time Udacity made changes to the upstream repo, as well. I could easily do comparison between our repo and the upstream Udacity repo and initiate a pull request from right there.

Sometimes, though, GitHub would throw up its hands and tell me I needed to merge conflicts else ware. My first stop was Visual Studio Code. I’m a fan of Visual Studio Code. I know a lot of purists cringe at the thought of using any sort of GUI git interface, but I like it and I think it’s a good option for those of us who don’t live on the command line on a daily basis. Not that I can’t hang with the command line, but I feel like I spend more time looking up what I need to do that way. VS Code’s merge tool was simple and effective and I enjoyed it… while it lasted.

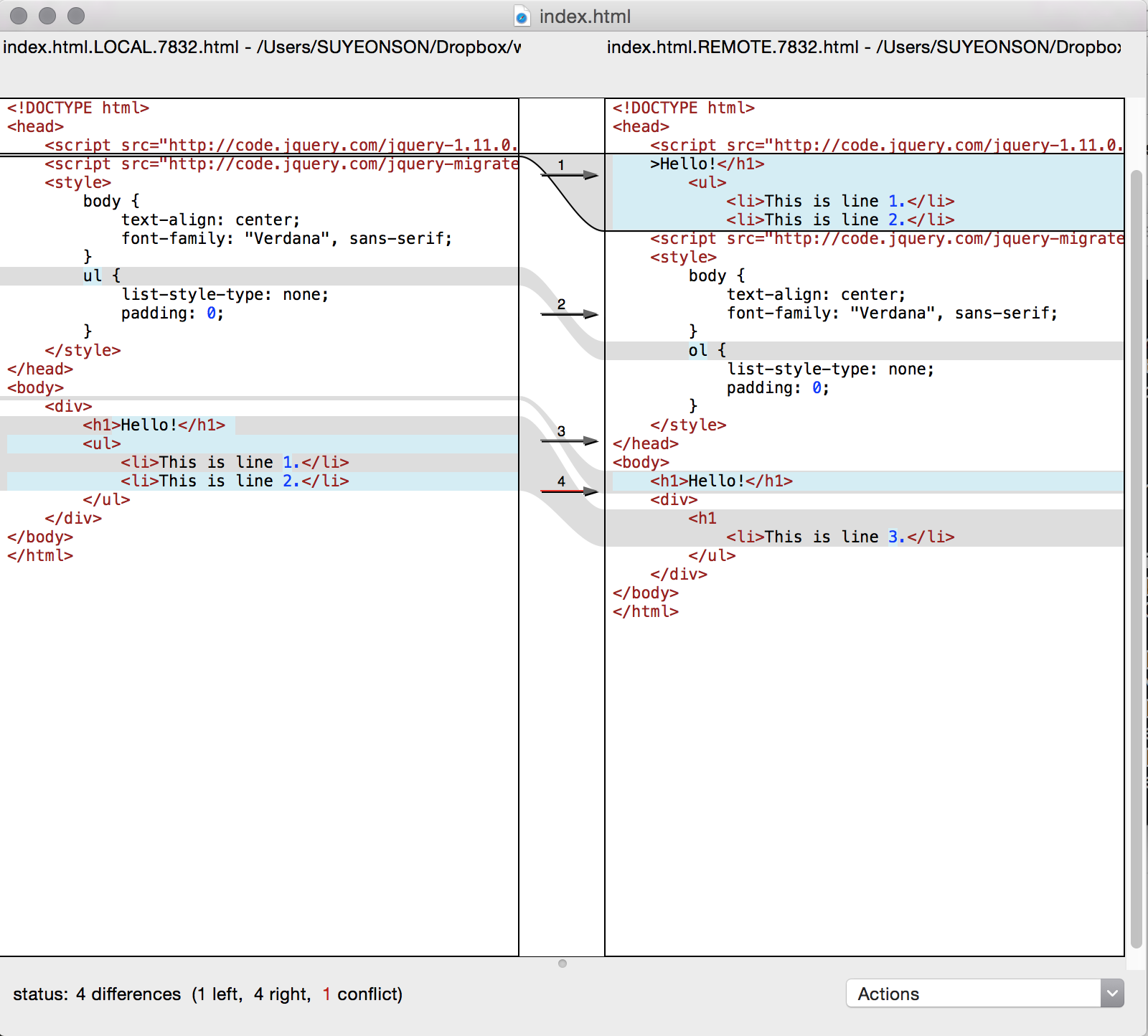

I don’t know what I did, but at some point I broke it and VS Code’s merge tool was all jacked up (as my toddler might say). I went to the trusty command line and it gave me a new merge option - the Mac OS default merge tool. I think it was called OpenDiff. Apparently it’s not especially popular, judging by the lack of recent screenshots available on Google image search, but it got the job done.

It might seem like small potatoes, but I feel like this was a great learning experience and probably a skill that will serve me extremely well in the future. Though I’ll probably dispense with the “Git Master” moniker… publicly, anyway.

Next time: Traffic Light Detector node!

The code for this project can be found on my GitHub.

UPDATE 2018-10-07 Yes, it’s been nearly a year, but I’m finally coming back to tie up this loose end. I’ll write more about what’s been going on in the meantime… hopefully not another, what, 10 months later. For now, allow me to put a bow on this as best I can remember.

So, after finding the Waypoint Updater and Drive-By-Wire nodes mostly taken care-of, it was on to the Traffic Light Detector node to see how things were going for Denise. She’s a seasoned veteran in robotics, so I did what I could to be helpful. The problem we faced didn’t have anything to do with being able to detect traffic lights and determine their states. It was the severe latency introduced running the ROS package in an Ubuntu VM alongside the Unity-based simulator on a Mac, for which, by all accounts it performed worst (and somehow this was the setup for myself and all of my teammates).

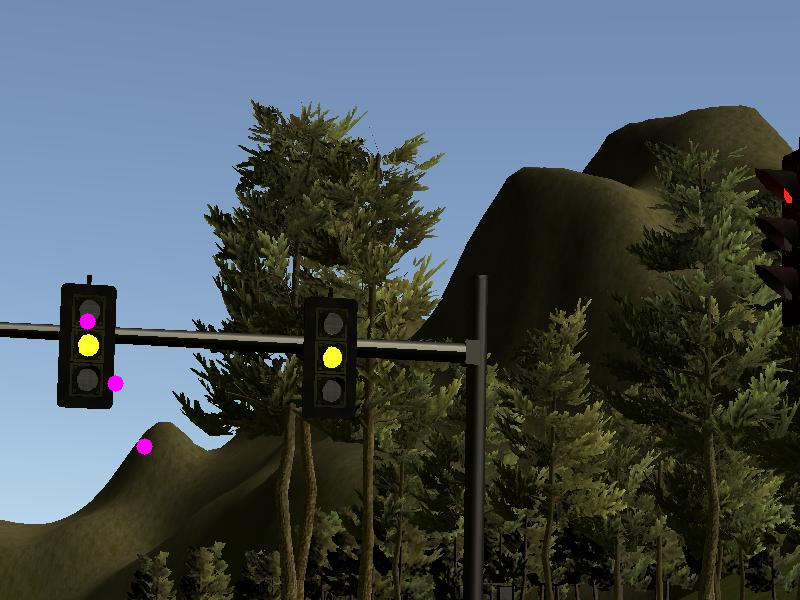

There was only so much we could do about the latency issues - we throttled various publisher nodes in ROS, fixed issues with the socketIO connection between the VM and the simulator, and other feeble fixes - but there was no way we were going to get it smoothly enough to run even the bare-bonesiest object detection on the camera image to find traffic lights therein. The best bet was a little-discussed, often maligned set of extrinsic camera parameters included in the project configuration. I say it was maligned because using them did no good - the parameters, when combined with a published set of traffic light locations and the formulas for extracting them from the camera images, produced an image location that was… misaligned. Completely. It was unusable, to the point that Udacity later ditched this as a method for determining the traffic light state completely.

I, however, was undeterred.

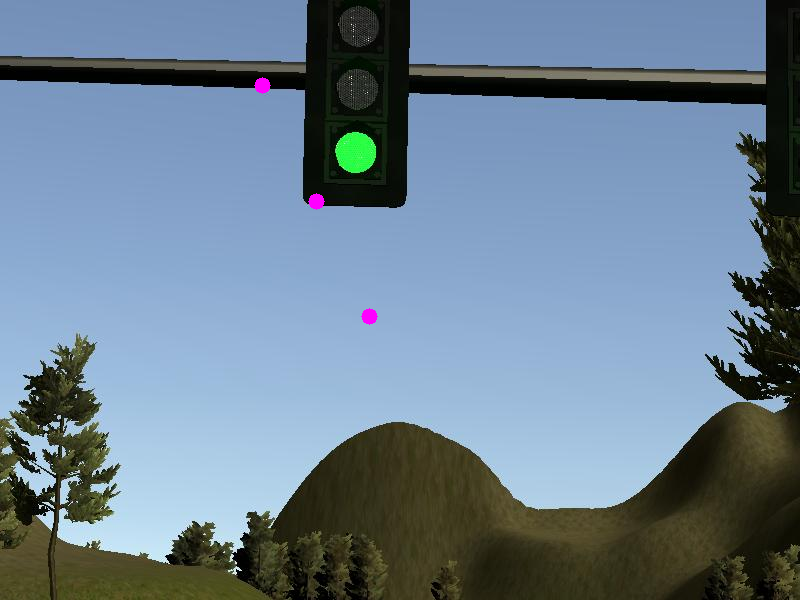

It took a lot of driving the car around in the simulator to different locations and facing the traffic lights, putting them in different locations in the image and then sort of reverse engineering the camera parameters. But little by little I was able to reliably find the locations of the traffic lights in the images, based on the published locations in 3D space.

From here, Denise was able to easily apply computer vision to determine the color of the light. In the end, the folks at Udacity didn’t grade the final projects too harshly since, obviously, they were still squashing some bugs. They did then take our code and run in on their own self-driving car, Carla. I would have liked to be there to see it, but our code, like several other teams, evidently, immediately caused the car to exceed its maximum acceleration and trip an emergency shutdown. Cest la vie. It was a bit of an anticlimactic end to an otherwise mostly thrilling experience, but it did provide me some great experience with a real-world ROS project (and all of its idiosyncrasies) and coding in a team environment. #TeamBacon4Life!

Ok, bye!